It was Wilder before Hollywood

Billy Wilder, screenwriter and director of the Golden Age of Hollywood, once said that "the best director is the one you don't see." True or not, Wilder’s iconic stamp on cinema is undeniable.

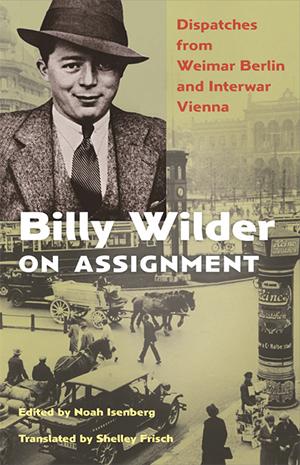

And now, RTF Chair Noah Isenberg has amplified our vision of the revered storyteller in Billy Wilder on Assignment: Dispatches from Weimar Berlin and Interwar Vienna—the first English-translated collection of Wilder's early journalistic writings, essays, interviews, and reviews. Isenberg’s introduction to the book, a version of which was recently published in The Paris Review, along with his commentary and photos of Wilder, situate these pieces (translated from German by Shelley Frisch) in historical and biographical context.

While Wilder's films such as Sunset Boulevard, The Apartment, and Some Like It Hot have been celebrated by critics and audiences alike, his witty and insightful writings may also be enjoyed starting April 27 from the Princeton University Press.

We asked Isenberg a few questions.

Q: What inspired you to bring attention to Wilder's early writings?

As a scholar of Weimar cinema, and a reader of German, I’d long known of Wilder’s early writings as a journalist. I’d drawn on them a bit in my earlier book on filmmaker Edgar G. Ulmer and in the liner notes on their collaboration on the late-silent classic People on Sunday (1930) for The Criterion Collection. But I always wondered why they’d never been translated into English. This is where the superstar, award-winning translator Shelley Frisch steps into the picture; we brought the project to Princeton University Press, and they immediately got behind the idea.

Q: Are there connections between these pieces and themes he explores in his films?

There are quite a few in fact, and I point to some of them in my introduction to the book: the early piece on the all-girl dance troupe The Tiller Girls arriving at Vienna’s Westbahnhof railway station (cue Marilyn Monroe sauntering her way to the train, in Some Like It Hot (1959), and the all-girl band Sweet Sue and Her Society Syncopators climbing aboard); another piece called “Berlin Rendezvous” in which the basic seeds for Wilder’s playful script of People on Sunday are planted; and an intriguing profile of director Erich von Stroheim featuring a discussion of Gloria Swanson in Queen Kelly (1932), which will enjoy its own private revival screening in Sunset Boulevard (1950), with Swanson as Norma Desmond and Stroheim as the former silent director and current butler.

Q: How do you see European perspectives intersecting with or shaping early Hollywood?

Wilder arrived in the U.S. in 1934 with little command of the English language, but with a burning desire to ace his way into the motion picture industry. His mentor Ernst Lubitsch had already struck it big, and he’d soon furnish the scripts, co-written with his American writing partner Charles Brackett, for Lubitsch’s Bluebeard’s Eighth Wife (1938) and Ninotchka (1939). Like Lubitsch, Wilder brought a European perspective to the work he did—the source material often harkened back to European novelists and playwrights—and as was the case with others in his cohort of European transplants in Hollywood (e.g., Otto Preminger), he had little patience for American puritanical values or for censorship of any kind. He often battled with the boys at the Breen Office (Production Code Administration), and much as he aimed at entertaining a mass audience, he was unafraid of offending the faint of heart.

Q: Wilder’s screenplays are peppered with sharp dialogue: was it hard for native German-speaking Wilder to transpose his thoughts to English? Do you see German influences in his characters’ voices?

From the beginning, because he was such a late learner of the English language (he is said to have acquired most of his vocabulary, not to mention the speed and rhythms of speech, from listening to sports broadcasters on the radio), he always collaborated with American co-writers: first Charles Brackett and later I.A.L. Diamond, with a few others (including Raymond Chandler and Ernest Lehman) in between. You can see traces of his Austrian-German past in quite a few of his films: the more obvious examples would be A Foreign Affair (1948), Stalag 17 (1953), and One, Two, Three (1961), but you can see more subtle allusions, and a European sensibility, even in some of his earliest work as a director The Major and the Minor (1942) and Five Graves to Cairo (1943), and Double Indemnity (1944).

Q: Why do you focus on studying filmmakers of the past?

That’s a big question. I think motion pictures are very much a part of our cultural heritage; this is certainly true of twentieth-century American history but also true in other regions of the world and at other moments in time. I think that filmmakers—like other artists, but perhaps even more so given the mass medium—engage with the world in which they work. In turn, they can help us to understand not only the artistic and formal achievements of their work, but the ways in which their work speaks to the larger socio-political debates occurring in their midst.